Crucible Team Theory: An approach to maximizing team performance in the shortest amount of time.

Author:

Kane Gyovai

Published:

March 01, 2025

Most of the great accomplishments throughout history are the result of teamwork. According to sociologists, large-scale cooperation is one of the primary reasons we have been able to advance from small tribes to a global civilization. Humans are an epic team. At a smaller scale, teams can be the stuff of legend. Seal Team 6, the Dream Team, the “miracle on ice” US Olympic Hockey Team, and many tech company founding teams including Apple (Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak), Google (Larry Page and Sergey Brin), and others might come to mind when thinking about high performing teams that accomplished hard things.

Teams are at the core of any modern enterprise. The success or failure of a mission, goal, strategy, or product can often be boiled down to how well the team undertaking the initiative performed. Due to the critical nature of teams within any organization, it's not surprising that various aspects of teams have been the subject of numerous studies and the cause for much hand wringing in management circles. When outcomes can be directly affected by team performance, optimization becomes critical.

The purpose of this article is to propose a new theory for optimizing team performance. While this theory can be applied to a team of any size, it was specifically developed for a team at the smallest, self-contained unit sometimes called an “atomic team”. Or, if you're Amazon, the “two-pizza team”. First, we will examine some preconditions that must exist for any high performing team. Next, I'll describe the most commonly held belief about team performance which I refer to as “Social Team Theory”. I'll then propose Crucible Team Theory and compare it to the prevailing theory. The last step will be to discuss the implications of this new theory so you can put it into practice and see your teams achieve their potential.

Disclaimer

The content presented in this article has not been subjected to rigorous scientific examination. I do not have enough concrete observational data to establish statistical significance for these claims. These views are based on my personal, and admittedly anecdotal, findings over the course of my life and career. You can think of this as an untested hypothesis.

Preconditions

Before we start, I want to establish two preconditions for high performing teams. These apply to any type of team regardless of size, composition, or domain.

- 1. High Integrity - Every member of the team has to be trustworthy, honest, and respectful. A team with even one individual who lacks integrity can result in dysfunction. This does not imply perfection. Every human is fallible and at times says or does something that is out of line or regrettable. For a team to function properly, those moments must be outliers within otherwise tightly clustered data points of transparency, good intentions, and respect.

- 2. Psychological Safety - There have been multiple studies that correlate team performance with how open the team can be without fearing negative consequences. Google's now famous Project Aristotle demonstrated this relationship and helped psychological safety go mainstream - especially within the tech community. The bottom line is, a team can only function properly if everyone on the team feels they can take well meaning risks without being punished. To get a sense of what the extreme opposite of psychological safety looks like, do some research on Chernobyl.

It's almost impossible to objectively evaluate team performance without those two preconditions being met because the absence of either precondition causes distortion effects that result in variability that is difficult to quantify but always limits performance. To put it simply, a team will never achieve their potential without these two foundational principles.

Social Team Theory

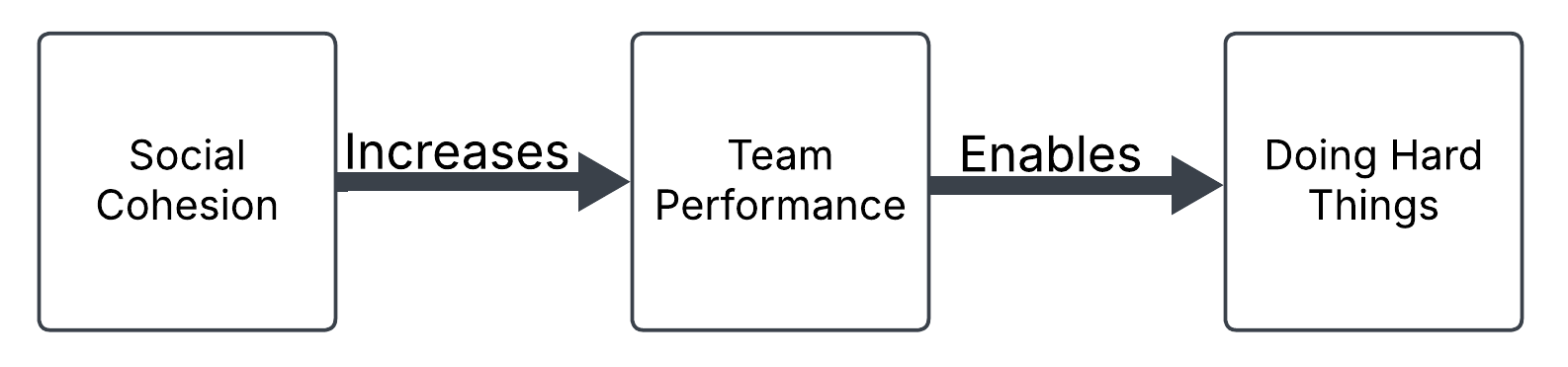

That brings us to the prevailing team theory of our time. This theory posits that if we all just “get to know each other” then performance will take care of itself. The idea is that getting to know each other on a personal and social level results in better team performance which allows the team to accomplish hard things together.

As the diagram suggests, the best way to enable a team to do hard things is for the team to increase its social cohesion. If you're reading this, you've almost certainly been on a team in which this theory was put into practice at some point in your professional career. The idea seems intuitive on the surface. As I'll show later in this article, this approach does tend to increase team performance over time. However, it does so relatively slowly. It also eventually results in a plateau that can only be overcome by doing hard things together.

Crucible Team Theory

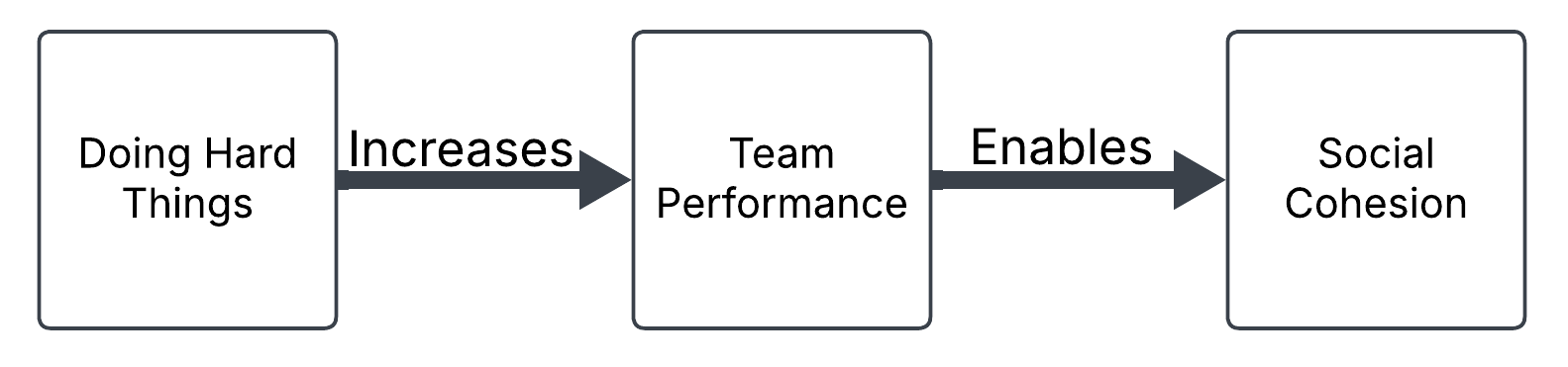

Which brings us to what is, in my opinion, a much faster and more effective way to increase team performance. The word “crucible” was selected to vividly capture the main premise of the theory which is: doing hard things together, often under pressure, rapidly increases team performance and improves social cohesion outside of the performance environment ( e.g. “work”, “competition”, etc).

What's that you say? Doing hard things before getting to know each other? Everyone knows that you have to be best buds with your teammates before you can truly hit your stride.

Except, you don't. There are many examples to substantiate this claim. Let's start with the military. Military units ( teams) are trained to perform at the highest level. How do they accomplish that? By getting everyone together to shoot pool, drink a few beers, and share life experiences? No. They start by completing grueling training programs and then build on that foundation to increase performance over time. In other words, they do hard things together.

Take another example of sports teams. We often see the comradery of teams in memes, on social media, or on sidelines at sporting events. What you don't see is what happened to get to that point. These teams train extremely hard together and by doing those hard things they grow closer. Reed Hastings, cofounder of Netflix, said teams at Netflix are like sports teams. Those teams perform better by doing hard things together.

Does that mean we should go around like robots trying to reach the pinnacle every day without uttering a single syllable that falls outside the scope of our goals? Of course not! Aside from the obvious fact of being fellow humans and sharing a planet together, social cohesion can significantly increase team performance.

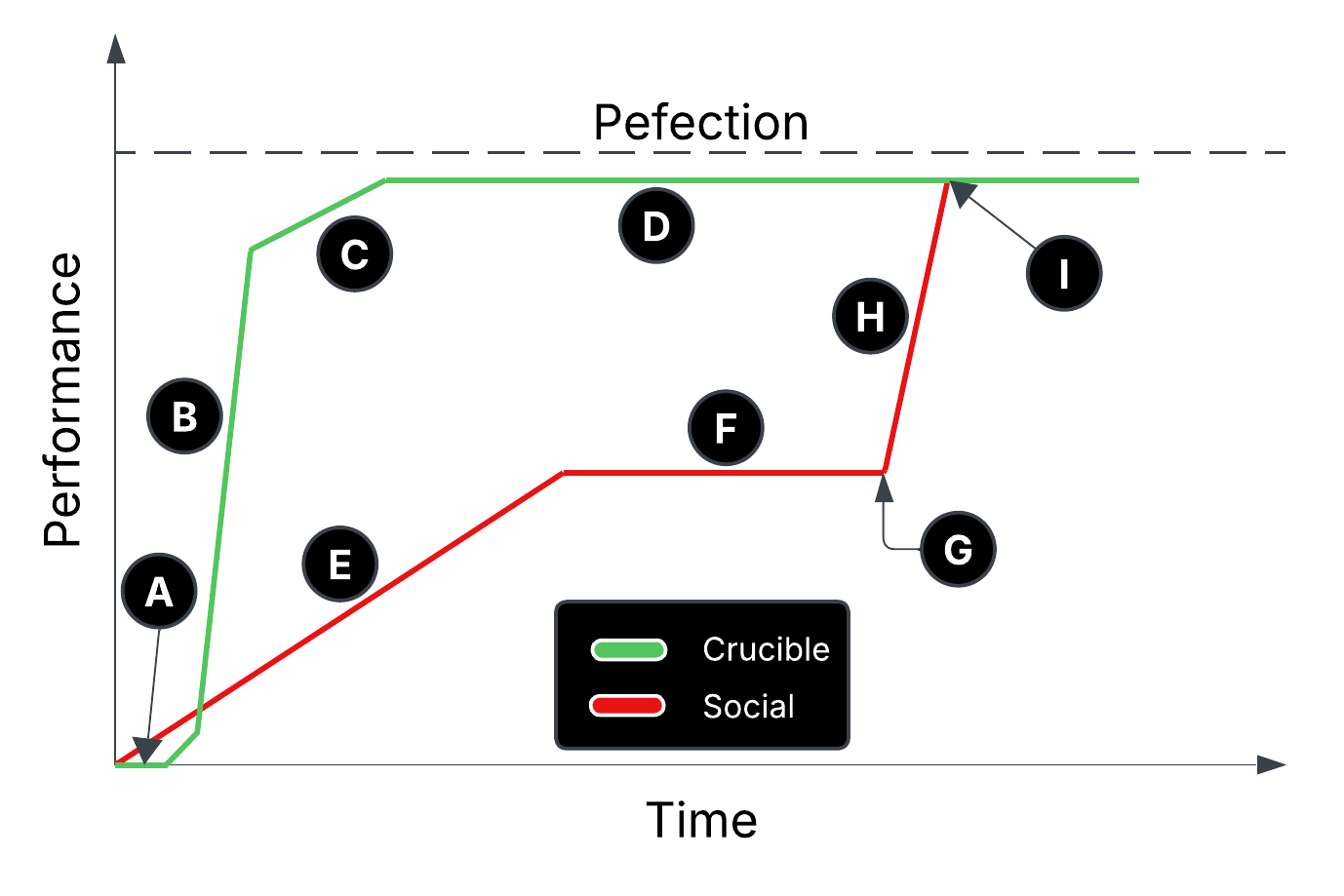

To illustrate these points, let's look at a direct comparison of team performance over time using these two theories. As I stated earlier, I don't have concrete data backing this illustration. Though I welcome that data from anyone out there if it does exist.

Let's break down what you're seeing in this figure. The first thing to notice is that perfection is unachievable. For those math or computer science minded readers, team performance is asymptotic in that it can continue to approach perfection without ever getting there. We don't need to examine why but suffice it to say teams are made up of fallible humans and perfection is incredibly hard to define. There are two other key points based on this representation of the two theories.

- 1. Crucible teams approach perfect performance much faster than social teams.

- 2. Social teams do eventually catch up to crucible teams but only after doing hard things together.

There are several other identifying features about the behavior shown in this figure. A description of each is provided for the corresponding data points which are labeled with letters.

- A - Growing Pains: Crucible teams are asked to do hard things together right away with only a limited understanding of the respective strengths and weaknesses of each team member. This results in flat-lined productivity in the short term but that is quickly overcome.

- B - Ascent: Team performance increases dramatically over a relatively short period of time as the team adapts to the composition of the team and starts to overcome the initial struggle of doing the hard thing.

- C - Social Cohesion: In doing the hard thing, the Crucible team members earn the respect of one another. That respect streamlines the social cohesion process and the social interactions result in a better understanding of one another which supplements performance.

- D - Plateau: Performance oscillates between slightly better and slightly worse with the average performance climbing subtly over time. The team has achieved optimal performance.

- E - Incremental Gains: The Social team gets to know each other through forced and impromptu interactions. The team gradually builds trust and learns more about each other's preferences, background, strengths, and weaknesses.

- F - Social Plateau: No additional performance gains can be realized through socializing. The team knows each other well but they haven't been asked to do anything hard together yet.

- G - The Hard Thing: Something difficult has been asked of the social team.

- H - Social Ascent: Performance increases dramatically as the Social team is asked to do something hard together. They build on the existing foundation established through social currency. Pressure and necessity result in difficult conversations and decisions that bring the team closer than ever before.

- I - Performance Intersection: The performance of the Social team finally catches up to the performance of the Crucible team. It follows the same plateau behavior described in D.

Implications

So what does this all mean and how can you apply this to your team(s)? Fortunately, it's straight forward. First, don't be afraid to have your team take on hard things. In fact, you must do that in order for the team to reach its potential. By doing hard things together, your team will not only increase its performance faster but the team will grow closer than they ever could have through social interactions alone.

Second, don't try to force social interactions for the sake of improving team performance. Teams will tend to reject this and it will become counter productive. Certainly, you should promote a culture of collaboration and open interactions but carefully consider any decision that results in forced interactions.

Lastly, think for yourself! That applies to any topic or domain - not just team performance. Don't accept prevailing theories or approaches in the business world at surface value without at least putting some critical thought into why those approaches are used.

Building Teams at BridgePhase

The principles of Crucible Team Theory are the foundation for BridgePhase's engineering culture. When recruiting and evaluating engineers, we ask ourselves “Can this person help us do hard things?”. That single question immediately establishes a high bar that can only be met with a well rounded skill set including technical aptitude, effective communication & collaboration, problem solving, thriving in ambiguity, organization, and time management. A gap in any of those limits a person's, and consequently the team's, ability to do hard things. Which is why we create custom, hands-on technical assessments for each technical role within the company. It's an important part of how we hire and how we build teams that help our customers accomplish their goals - especially when those goals are hard to achieve.

Conclusion

Andy Jassy once said “there is no compression algorithm for experience”. While that holds true, experience can be a compression algorithm for team performance. Especially if that experience comes from doing hard things. So the next time you're trying to find ways to improve team performance, ask yourself “What hard things have we done lately?”.